The Story of Systems: chapter III

How do you see the system you want to change?

To paraphrase the 19th Century novelist Marcel Proust:

“The only true voyage of discovery…would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes”

That’s exactly what we need to see systems:

other eyes;

other ways to see;

And, because our particular species of primate likes making tools, we’ve invented some to help us see: the who, what, where, and when of systems.

Come with us into this story.

Make your favourite drink and get comfortable.

It’s a story that can’t be told quickly.

But it’s worth hearing…

Who

Our favourite tool to see the who of systems change, is Two Loops from the Berkana Institute.

The story of Two Loops goes a little like this:

As a new system rises and the dominant, business-as-usual, system declines and falls, as all systems do in the end (think Roman empire), the people in the system play their own roles in systems change.

Pioneers decide to disengage: to break away from the dominant system and start imagining something new; something better. They’re separated, and feeling alone

Later, the lonely pioneers begin to form networks with other like-minded souls. They start to find the confidence that they’re on to something. It’s nice to have the solidarity of meeting other people with a divergent vision of the future

Over time, the networks start to get organised. They start to form a community of practice to intentionally create a movement for change and share their work to nurture a new, emergent, system

Meanwhile, the stabilisers (or stewards) live within the dominant system and can see how things are changing. They keep the dominant system stable whilst, at the same time, they enable experimentation with the new

Champions are the first to jump the gap between the old and the new, starting a practice of bridge-building when the emergent system is sustainable enough for it to truly replace the old, tired, dominant system

All the roles are needed to change a system. Which role are you?

What

The what of systems change is beautifully described by Six Conditions of Systems Change, from The Water of Systems Change written by John Kania, Mark Kramer, and Peter Senge.

It shifts our focus to the conditions that hold the dominant system in place, so we can figure out what to work on if we want to change a system.

It looks like an iceberg:

The three elements in the top layer (policies, practices, resource flows) are explicit, like the visible part of an iceberg: you can see them. The middle layer (relationships & connections, and power dynamics) is semi-explicit: you catch glimpses of it but it’s not always clear or obvious. And the deepest layer (mental models) is the hardest to see: it’s deep enough and dark enough to need a long time for your eyes to adjust. It is implicit.

In the Six Conditions model, the explicit layer is where we see the visible, observable reality of life:

Policies:

Government, institutional and organisational rules, regulations, and priorities that guide their own and others’ actions

Practices:

The activities and habits of institutions, coalitions, networks, and others. It describes what they actually do, rather than what they say they should do

Resource Flows:

How money, people, knowledge, information, and other assets such as infrastructure are allocated and distributed

In the middle layer we find the conditions that are less visible, yet still act as a glue to hold problems in place:

Relationships & Connections:

The quality and strength of connections and communications amongst people and organisations in a system, especially among those with shared interests

Power Dynamics:

The distribution of decision-making power, authority, formal and informal influence among individuals and organisations

Finally, foundationally, and deepest of all, we encounter the conditions that are acting out of sight and sometimes out of mind:

Mental Models:

Habits of thought. Deeply held beliefs, assumptions and ways of operating that influence how we think, what we do, and how we talk

Where

The where of systems change is a question in more than one part:

it’s about seeing the system that you want to change;

seeing where you fit in that system;

seeing where and how you are influenced by, and influence, the system; and

for the future, figuring out where to intervene to change it

The tool we humans have invented to answer the where questions is not new.

It’s a map.

And, like any map, it tells you what’s important, and how everything is connected, but unlike any map; it also tells you what causes what.

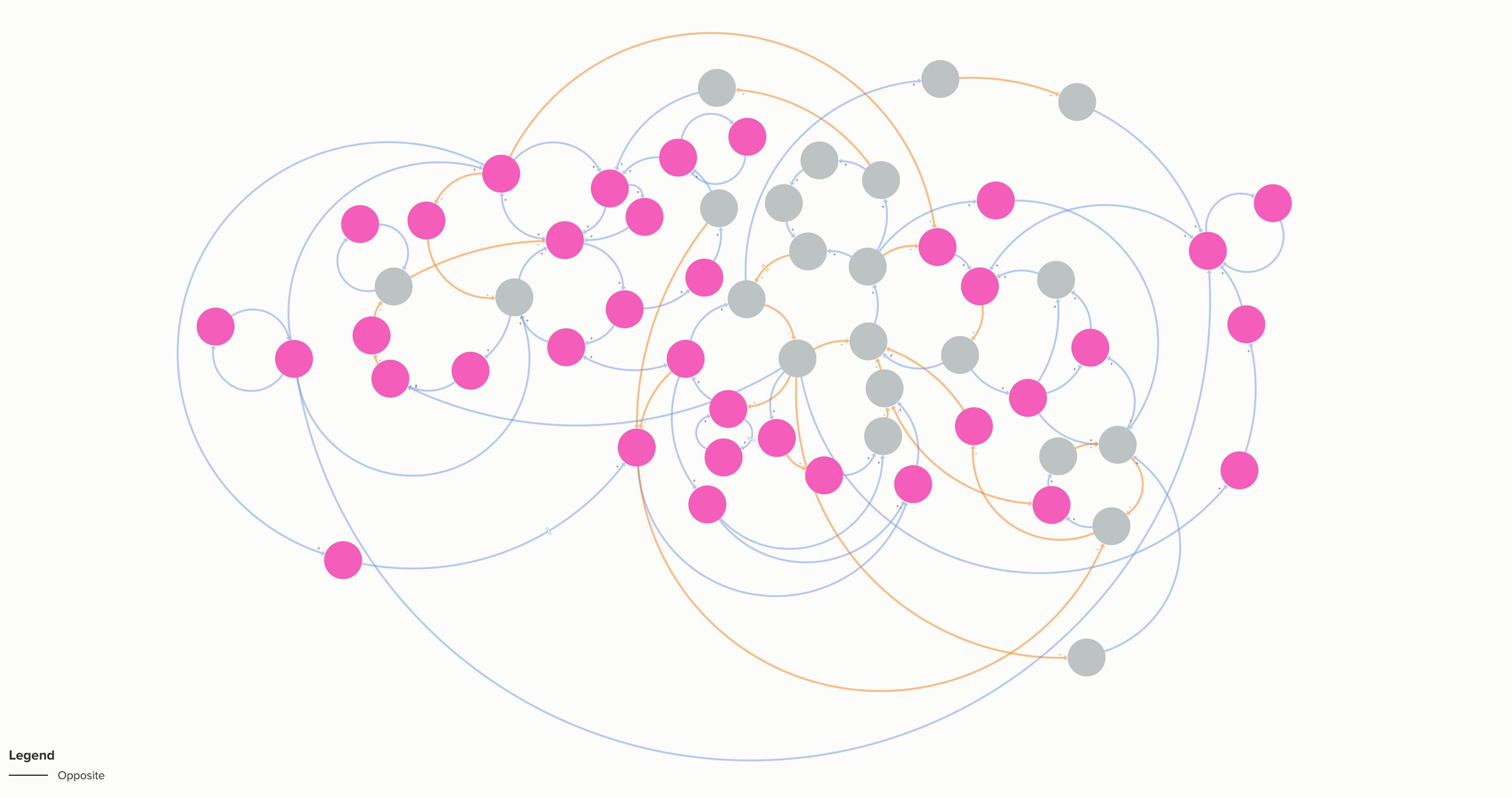

Take a moment for your eyes to adjust. Let’s take a look:

This example is one we made for the housing system in the UK and, for this explanation, we’ve deleted all the clutter of descriptions and labels so it’s easier to see the big shapes.

If you zoomed-in, you’d be able to see the story of how some of the loops work.

An example might be the story of housing wealth dependency. In words it might go like this:

“as house prices go up, the wealth of owners goes up; and

as the wealth of owners goes up, the reliance on housing wealth goes up; and

as reliance on housing wealth goes up, the political protection of home ownership goes up (who’s voting for a politician that’s going to take away the wealth you have stored up in your home?); and

as the political protection of home ownership goes up, tax policies to protect asset wealth get stronger; and

as tax policies to protect asset wealth get stronger, investor demand for investment property rises; and

as investor demand for investment property rises, house prices go up (because there is more money chasing houses to buy); and

go back the start, and repeat…”

As a causal loop, that looks like this:

…and the whole map is just a connected set of loops like the one in our example, revealing the whole system and how everything is connected.

Which means we can now see the system, see where we are in the system, see how we’re influenced by it, see how we influence it, and ask where we can intervene to change things for the better.

We’ve chosen an example that happens to be about the UK housing system, but systems maps are a tool you can use for any system, to figure out the where of systems change.

When

Last stop on our tour of our favourite systems tools is about the when of systems. It’s a way of seeing systems change over time. It’s called Three Horizons, although we’re fond of the subtitle given by its inventor, Bill Sharpe: The Patterning of Hope

Three Horizons tells a story of how systems change over time in response to a different imagination of the future: of the possibility of a better world than the one we have; and the innovation it will take to translate that vision of the future into a new reality:

We start with a Horizon 1 - the world as it is. When we look around at the world, this is the thing we see: the status quo, the most prevalent model, the dominant mindset right now. As time elapses and things evolve it is expected, guaranteed, to decline

At the same time, in Horizon 2, innovators are doing the good work of starting up new practices and inventing new solutions to challenge the status quo and solve existing problems in new and better ways. Over time, these innovations scale and grow, replacing the out-dated status quo

Our third lens is Horizon 3 - the best version of the world we all want to see, the imaginative, hopeful vision of the future we want to create. Over time, it is such a compelling story that it replaces the old ideas and becomes the dominant new mindset

It’s important to notice that all three horizons are present in a system at once: it’s just easier to see some of them than others.

Early on, it’s hard to find glimpses of future thinking amidst all the sound and fury of the status quo. But, over time, as a new, hopeful, imagination of the future becomes the new normal, then innovation explodes into view and turns the world upside down with new ways of doing life. Think renewable energy, or electric cars: unthinkable not so long ago but fast becoming the unstoppable new normal.

Which horizon are you in?

“There are good reasons for suggesting that the modern age has ended. Many things indicate that we are going through a transitional period, when it seems that something is on the way out and something else is painfully being born. It is as if something were crumbling, decaying and exhausting itself, while something else, still indistinct, were arising from the rubble.”

Epilogue

One final thought about our favourite systems tools.

Their purpose, indeed, the distinctiveness of systems thinking, is synthesis. Not analysis. None of these tools is trying to dissect complexity into manageable components, because systems cannot be understood that way. Analysis is the answer to a different question, and it’s a habit that takes time and practice to un-learn. Instead, systems tools are trying to help us see the whole picture; join the dots; understand the and.

In a rather beautiful example, the most powerful tool you’ll be using to think about systems, is itself a system that can only be explained by systems thinking (!) It’s your brain. It’s a brain made of neurons, which analysis tells you have a really simple job: they send signals to other neurons across the connections between them. Simple. Neurons are perfectly reliable, consistent, and predictable. But almost nothing about a neuron tells you how a brain works…until you understand the and. It’s the connections and interactions between the 86 million neurons in your head that create something no neuron can explain: consciousness; memory; thought.

Happy systems thinking.